A recent AP exclusive entitled “How candy makers shape nutrition science,” opens with a reference to a 2011 paper that outlined a surprising scientific finding: Children who eat candy tend to weigh less than those who don’t.

Naturally, that paper received a lot of coverage. It was just what some folks wanted to hear. In its report “Does candy keep kids from getting fat?” cbsnews.com acknowledges this in a whimsical closing comment: “…for those who have tried to stymie a sweet tooth, this news isn’t just reassuring. It’s sweet.”

It turns out that AP re-visited this 2011 study and paper as part of its investigation into how food companies influence thinking about healthy eating. They sifted through thousands of pages of emails to uncover some not-so-surprising findings.

For starters, the paper was funded by a trade association representing the makers of Butterfingers, Hershey and Skittles. And as AP reports, the candy study was drawn from a government database of surveys that asked people to recall what they ate in the past 24 hours. In a section about the study’s limitations, authors of the paper stated that the data “may not reflect usual intake” and that “cause and effect associations cannot be drawn.”

AP’s investigation uncovered an email in which one of the paper’s co-authors—a professor of nutrition at Louisiana State University—made the following comment: “We’re hoping they can do something with it—it’s thin and clearly padded.” It ends up that these facts did not interfere with the successful marketing of the study.

As we wrote about in a previous post, studies are powerful marketing tools for major food corporations, special interest groups and lobbyists. They earn media. They start conversations. They influence consumers’ purchasing decisions. Most people are unaware of the heavy-hands shaping the direction of studies and outcomes.

Professor, author and world-renowned expert in nutritional sciences, Marion Nestle has made it her mission to shed light on the bias and lack of transparency in nutrition research. On her site Food Politics, she tracks industry-funded studies with industry-favorable results.

With a highly trained eye, Nestle can spot a bogus, “marketing fluff” study immediately. But considering the conclusion of the candy study, shouldn’t we all be on to this by now? It would seem so, until you consider the fact that we’ve been exposed to biased claims our entire lives.

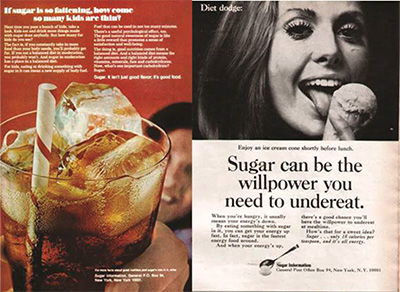

In an article entitled “A Timeline of Sugar Spin,” Mother Jones dates the phenomenon back to the 30’s. Take a look at these two advertisements from the early 70’s:

Does the headline of the first ad sound familiar? Over 40 years later, the same message is still getting traction. Sugar doesn’t make you fat, it makes you thin. The difference? It used to just be advertising copy, now it is presented as a scientific research finding.

Sugar interests still maintain that sugar has never been proven to cause health issues. Considering the rise in diabetes, obesity and other chronic conditions, how likely is their claim? Based on the findings of British professor John Yudkin, published in 1972, we see more to the story. Stay tuned.